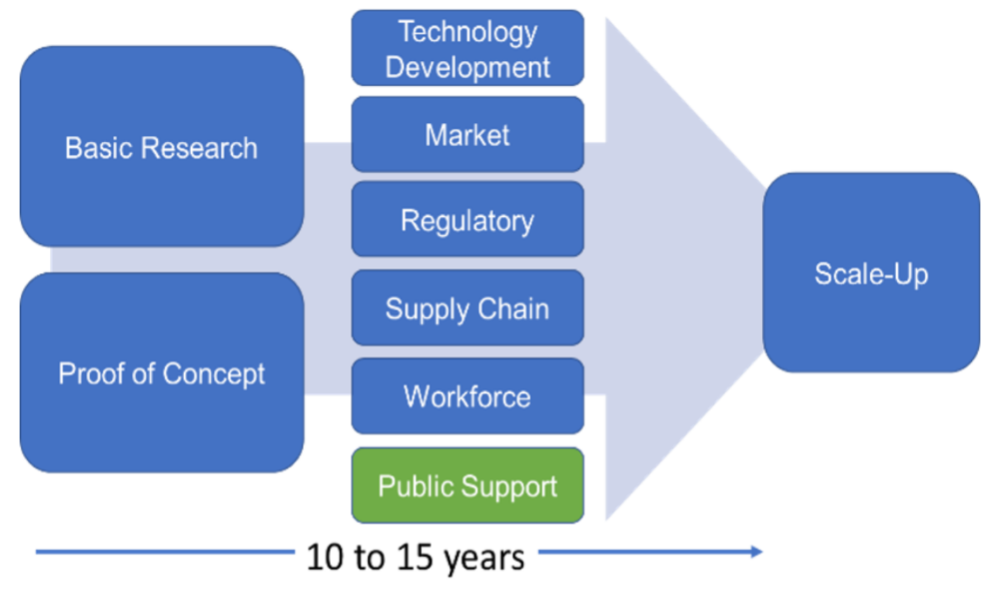

What Does It Take to Commercialize Fusion?

“What does it take to commercialize fusion?” is really the “trillion-dollar question”, and I don’t utilize the milestone “trillion-dollar” lightly. The forecasts in the upcoming Ignition Research report predicts exactly that annual value of the fusion energy market, as measured by the construction and initial equipment costs to build the fusion power plants forecasted by 2050. Fusion energy is the biggest economic transition on the horizon in the developed world for the mid-21st century, and like similar infrastructure transitions, it will take policy initiatives as well as public and private investments to make it happen.”

The policy side of things, approaches such as favorable tax treatment for fusion R&D and commercialization expenditures can help speed the progress of these efforts, as can grants to stimulate the commercialization of “fusion-centric” technologies such as high-temperature semiconductors (HTS), thermal blankets, high-energy lasers, high-vacuum pumps, and next-generation power capacitors for charging both lasers and HTS magnets are also critical to ensure that we progress these technologies from “one-off” prototype development and into the building of a real industrial supply chain for fusion quickly and effectively.

Additionally, there are non-financial government initiative programs which can have large positive (or negative) impacts on fusion, including:

- Regulatory Regimes: Hitting the right balance of regulations for emerging markets is not a simple matter. For instance, applying safety and proliferation regulations similar to the ones for the nuclear fission energy industry would likely cripple fusion energy, largely because these issues are very different between the two industries. On the converse side, the inclusion of initial costs of fusion powerplants in electricity rates is very much like nuclear fission – both involve large up-front investments, and fairly low ongoing fuel costs.

- “Made In The USA” Requirements: The question here is to what extent our fusion technology needs to be “100% American”. Avoiding an adversarial supply chain, particularly with China, Russia, and other “banned” countries is obviously desirable. However, expecting that we can do it alone is probably unrealistic. Regulatory regimes that enable working with our allies are preferable, even if this means that we do not own the entire “tech stack”.

Finally, there is a big difference between building the first prototype fusion power plants, and building ten commercial fusion power plants (or more) a month. This is why standardization and interoperability efforts are so critical in the development of a successful fusion ecosystem.